He would not be content with just use photography to record a scene but rather seek, in his own works, to "avoid the mean, the bare, the ugly, and to aim to elevate the subject, to avoid awkward forms and to correct the unpicturesque". In that, and in the connection he felt existed between the classics, poetry and photography - as a source for themes and settings -, he shared the standards of academic nineteenth century painting and meant to apply them to the new art form.

Technique

Robinson wrote many treatises in his lifetime, including Pictorial Effects in Photography: Being Hints on Composition and Chiaroscuro for Photographers, published in 1869, where he used the term "pictorial" in relation to photography for the first time. In his view, the use of techniques such as "combination photography", created by himself - consisting in the combination of separate images into new ones by manipulating the negatives or prints - supported his claim that photography was a "High Art": only through the artist's direct intervention, his/her ingenuity and creativity, the final image came to be. The application of pictorial techniques, such as the chiaroscuro - the use of dramatic lighting and shading to convey an expressive mood - was a powerful tool in the hands of the photographer.Remarkable images... Debated images

Robinson created some of most remarkable manipulated images in the nineteenth century. His aesthetics were influenced by John Ruskin's, trying to create moments of timeless significance.Fading Away, Robinson's most famous image, is a composite print of five negatives. It was called by one critic "an exquisite picture of a painful subject". The model for both She Never Told Her Love and Fading Away is Robinson's favourite, Miss Cundall.

The second, purportedly showing a young consumptive woman surrounded by family in her final moments, was subject to heated debate that, in some ways, continues now. Accusations of indelicacy that are maybe still familiar to the contemporary ear - the invasion of a eminently private moment, that of death - were combined with those of dishonesty - the use of a truthful medium to create a false image - and bandied around the composition.

However, there is no difference in amount of "artificiality" between this photograph and any painting representing the same subject, tying both media neatly together as attempts to elevate life to art and transcend the moment. Also, given that tuberculosis was endemic among the urban poor and not so much among the wealthy and well-to-do, the accusation or artificiality can also be levelled at Victorian art in general. Searching to elevate the subject, Victorians altered reality - inexcusably, from the point of realism - as they refused to depict what surrounded most people living in industrial-revolution England: squalor, but then that would have been considered even more indelicate.

In any case, the picture received royal approval in that Prince Albert not only bought a copy of Fading Away, but also ordered every composite print Robinson created afterwards.

|

Henry Peach Robinson, She Never Told Her Love, 1857. Albumen Print. This solitary figure, is a photographic representation of unrequited love. The title is derived from Shakespeare's Twelfth Night (II,iv,111-13): She never told her love/ But let concealment, like a worm i' the bud,/ Feed on her damask cheek. As cloying Victorian representations of excessive feeling go, this one is perfectly discreet, capturing the unimportance of the external world when the mind is consumed by an overpowering emotion. There is no gesticulation, no artificiality in the pose. The almost black background captures de isolation of the wan figure, that would serve as a study for the central figure in Fading Away. [Source: George Eastman House] |

|

| . Henry Peach Robinson, Fading Away, 1858. Albumen print, combination print from five negatives. Only 200 prints were made of the photographs, as an assistant accidentally ruined the negatives. The title is a verse from one of Percy B. Shelley's poem Queen Mab: There is a nobler glory which survives/ Until our being fades, and, solacing/ All human care, accompanies its change;/ Deserts not virtue in the dungeon’s gloom,/ And in the precincts of the palace guides/ Its footsteps through that labyrinth of crime;/ Imbues his lineaments with dauntlessness,/ Even when from power’s avenging hand he takes/ Its sweetest, last and noblest title -death. [Source: George Eastman House] |

|

Henry Peach Robinson, Fear, ca. 1860. Albumen silver print. [Source: Metropolitan Museum] |

|

Henry Peach Robinson, Dawn and Sunset, 1885, printed 1890. Photogravure, from "Sun Artists, Number 2". In his influential book The Elements of a Pictorial Photograph (1896), Robinson wrote: "A great deal can be done and beautiful pictures made, by the mixture of the real and artificial in a picture. It is not the fact of reality that is required, but the truth of imitation that constitutes a veracious picture." [Source: Art Institute of Chicago] |

|

Henry Peach Robinson, When the Day's Work Is Done, 1877, printed 1890. Photogravure. [Source: Google Art Project] |

|

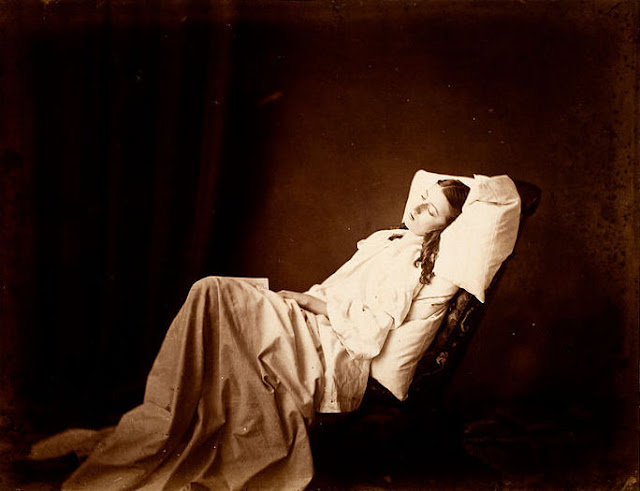

Henry Peach Robinson, Sleep, 1867, albumen print. Robinson used as inspiration a poem by Matthew Arnold, Haworth Chrurchyard, 1855 (Sleep, O cluster of friends,/ Sleep! or only, when May,/ Brought by the West Wind, returns/ Back to your natives heaths,/ And the plover is heard on the moors,/ Yearly awake, to behold/ The opening summer, the sky,/ The shining moorland; to hear/ The drowsy bee, as of old,/ Hum o'ver the thyme, the grouse/ Call from the heather in bloom:/ Sleep, or only for this/ Break your united repose). Some paragraphs in the poem refer to Charlotte Brontë and Harriet Martineau, while others at the Brontë siblings. [Source: Better Photography]. |

George Eastman House 1000 Photo Icons, p 358-60. Taschen, 2002.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Henry Peach Robinson

Wikipedia and Wikimedia Commons

George Eastman House Artful Ambitions/An Art of Its Own

Henry Peach Robinson, the Pictorialist, by R. Lalwany.